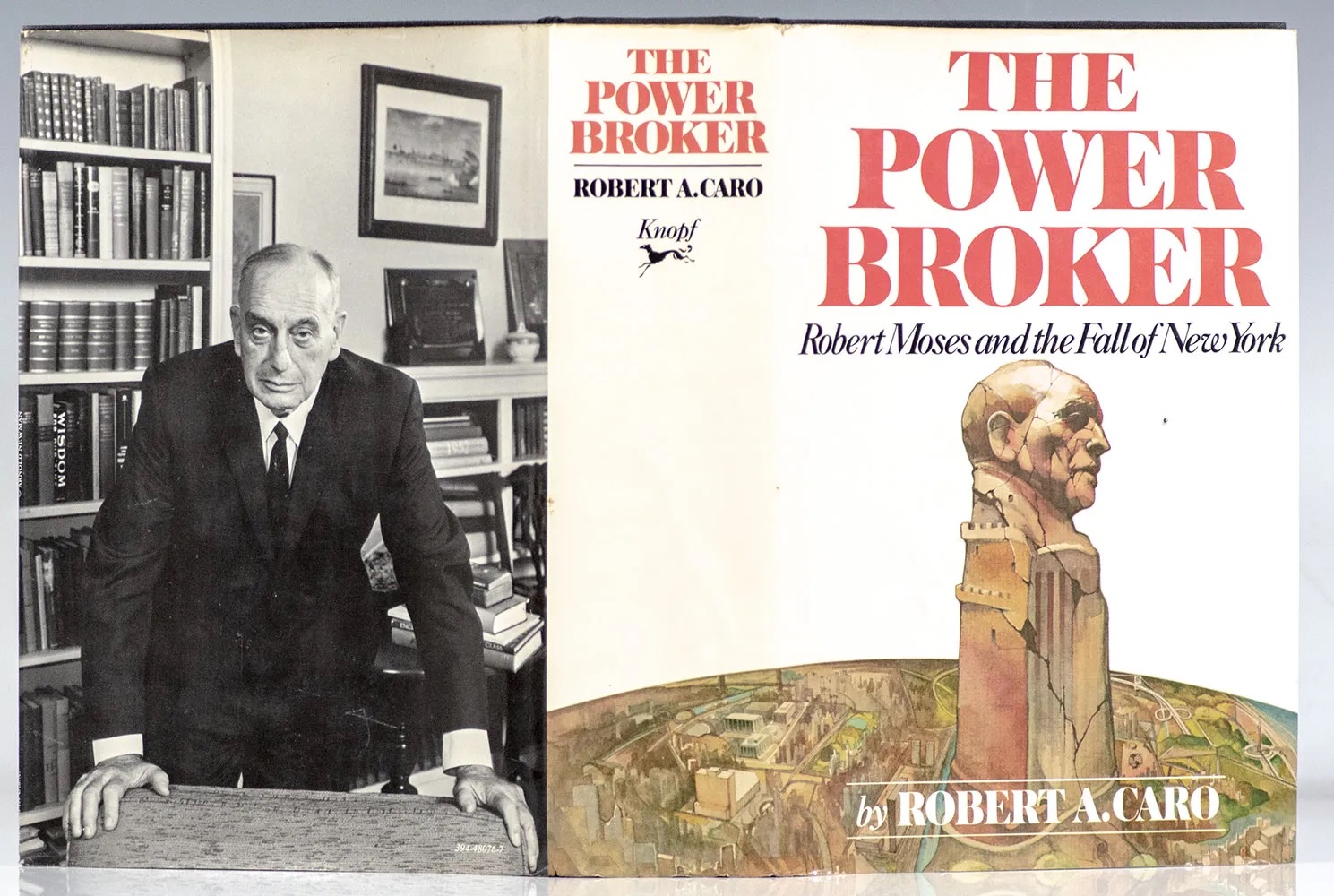

I love the Power Broker and I knew Moses had replied about the book, when I went to read it thou it was a little tough so here is ChatGPT transcribed version. Original source: https://eportfolios.macaulay.cuny.edu/seminars/glassman08b/wp-content/uploads/2008/02/moses-response-to-power-broker.pdf

COMMENT ON A NEW YORKER PROFILE AND BIOGRAPHY

ROBERT MOSES

Robert A. Caro has written a biography about me, excerpts from which have appeared in a four-part Profile in The New Yorker. The Profile seems to be a considerably digested, amended, edited, and expurgated version of the twelve-hundred-page biography. I have sought the advice of close friends, most of whom told me to say nothing. On the other hand, judging by inquiries, some comment seems to be called for. I have limited it to less than 3,500 words as against 120,000 in the Profile and 600,000 in the book. I shall have nothing further to add, except to suggest that the critics remember Governor Smith’s favorite remark in such contexts: “Let’s look at the record.”

It is difficult to address oneself at once to a whitewashed, Bowdlerized Profile with a sensational, eye-catching title calculated to attract curious readers, and a biography. The Profile is within the bounds of current journalistic practice. The biography, on the other hand, is full of mistakes, unsupported charges, nasty, baseless personalities, and random haymakers thrown at just about everybody in public life. The biography tries to prove that I was a good boy who fell from grace, became a politician, and mistreated the poor. The author can’t even get the names and places straight. There are hundreds of careless errors. Many charges are downright lies, manufactured by early opponents who have waited for an opportunity to satisfy ancient grudges and found this author a ready instrument. Among the personal, nasty, false, venomous, and vindictive canards is one that I was romantically linked with Mrs. Ruth Pratt, our first Congresswoman, and that as a result, my wife took sick, became an alcoholic and a recluse, that I virtually abandoned her, joined some kind of foursome, and took a lady who subsequently became my wife to Florida. My companion on the short Florida vacations was my daughter, Jane. With respect to my family life, the author’s innuendos are wholly untrue and scurrilous. Under the fair libel laws, they would be actionable.

For dirt and misinformation, the author says he latched onto a brother of mine, now dead. Similarly, he attacks by name, and by sly hints of wrongdoing and conflicts of interest, scores of prominent and respected officials and citizens, many of them dead. The author praises two reporters, Gleason and Cook of the Scripps-Howard press, as sterling representatives of the journalistic profession but fails to inform his readers that they were called in by the district attorney and fired in disgrace after being forced to admit that they had fabricated a particularly vicious housing story.

I invite no prolonged controversy with the likes of Caro and his publishers. This comment is not meant to spark controversy. It aims to make one statement which will answer legitimate inquiries. If there were the slightest vestige of truth in the random charge that poor, helpless, displaced persons met ruthless public works dictators who sadistically scattered them to the worst rookeries, why do not Caro and his publisher offer some plausible evidence? Ninety-eight percent of the ghetto folks we moved were given immeasurably better living places at unprecedented cost. Usually, a month after the last relocation, not a letter of complaint was received.

And what in ordinary English is the meaning of the words “Power Broker”? What is a power broker? Does Fleischman of The New Yorker or Knopf, the publisher, or Caro, the snooper, mean that I profited financially? If that’s the implication, why don’t they say so? Do they mean I have been what in common political parlance is called an “operator”? And what is an operator? Someone who is devious, serpentine, and intractuous? Do these publishers use such words simply to attract gullible purchasers regardless of what there is between the covers?

As to whether honest public service is a profitable profession, let me say that I spent most of my principal in order to remain in public employment. The story of my wealth is fiction. I had to borrow money from my mother to persuade busted contractors to bring back material in order to open Jones Beach on time. I had to dun friends to keep survey parties from starving when our enemies cut off our funds in the State Legislature. These tidbits escaped the author, Knopf, and Fleischman.

There is no reliable evidence to be obtained from a few landowner malcontents who profited less than they expected from our improvements. To find out whether there were any sizeable numbers of families displaced to accommodate parks, parkways, bridges, tunnels, power developments, and suchlike, it would be necessary to make a thorough impartial canvass, not to interview a few bellyachers at street corners or disgruntled truck farmers on the edge of the City about to make hundreds of thousands of dollars from proximity to new roads.

It would also be essential to determine whether any growth or prosperity on Long Island east of the City line would have been possible without the facilities for travel we built and what could have been substituted for cars, trucks, and buses running on rubber and paved roads. One cannot help being amused by my friends among the media who shout for rails and inveigh against rubber but admit that they live in the suburbs and that their wives are absolutely dependent on motor cars. We live in a motorized civilization.

The current fiction is that any overnight ersatz bagel-and-lox boardwalk merchant, any down-to-earth commentator or barker, any busy housewife who gets her expertise from newspapers, television, radio, and telephone, is ipso facto endowed to plan in detail a huge metropolitan arterial complex good for a century. In the absence of prompt decisions by experts, no work, no payrolls, no arts, no parks, no nothing will move. Honest public officials will be denounced as wheelers and dealers, oppressors of the poor, dictators, fixers, and power brokers intolerable in a true democracy. Officials who are not thin-skinned and have the courage of their convictions pay little mind to the gravamen of such charges and don’t bother to answer allegations at length or defy all alligators.

What with poisonous critics, savage commentators, public relations advisers, speech and ghost writers, and equal-time rebuttal spouters over the air, we are rapidly succumbing to what Whitney Griswold of Yale used to aptly call “nothing but technological illiteracy.” On the other hand, you don’t catch us miniscule imitation Napoleons denying open forums for dissidents to find fault and enthusiasts to advocate causes. We simply ask that the forums be properly conducted. Other victims of biographies have survived harder impeachments. Critics claim to be anxious over the influence of petty dictators dressed in a little brief authority. On the other hand, builders worry about government paralyzed by lunatic fringes.

In this context, I think of that kindly fuddy-duddy, British Poet Laureate Sir William Watson, who was much too decent for the critics. He was roused to fury only once. That was when he could no longer stand the gibes of the wife of a Prime Minister and burst out with the best verse he ever wrote, beginning: “She is not old, she is not young, The woman with the serpent’s tongue.”

Here and there in the Profiles, there are broad hints that my associates and I were not always ultra-refined in our actions. They complain that we have not followed the Marquis of Queensberry rules. They say that on occasion we quietly, after hours, smoothed the paths for our parkways. They insinuate that old trees were whisked away by ingenious stump pullers to allay the apprehensions of nervous environmentalists. If this be true, tell it not in Gath. Publish it not in the streets of Askelon. As the city folk ride into the open country, we shall, I trust, be forgiven. The original railroad builders, too, were in a sense fuel merchants and chopped down some spindly woods to stoke their engines.

By way of contrast, I like to reflect on the approach of one of our own distinguished American philosophers and all-around tongue-and-bat athletes, Leo Durocher. Perhaps in mild extenuation of his own occasional lapses from Amy Vanderbilt’s rules of etiquette, Leo wisecracked, “I really believed his own architectural interruptions of nature lifted us to the hills whence cometh our light, enhanced the plains, and swept us out to the limitless seas.” Frank’s comparison of himself as a skylark and to me as a blind night crawler was, of course, just a quaint bit of Celtic humor. We take these things from the Frank Lloyd Wrights because we admire them in spite of their idiosyncrasies.

Those of us who have comparatively little time left for constructive work and have to husband our resources cannot afford to waste muscle on keyhole snoopers, dirt dishers, gossips, and embittered bums trying to get a hunk on someone they dislike.

In all patriotic yarns, there is supposed to be a hero like Arnold von Winkelried who gathers the spears of the enemy to his bosom and saves the Swiss Navy. The role is not for me. The spears in this instance are made of the paper we elegantly know as bunwad. They crumble on contact.

The New Yorker Profile series ends with these remarkable sentences: “It is impossible to say that New York would be a better city if Robert Moses had not shaped it. It is possible to say only that it would be a different city.” Assuming that the City changes, however brought about, were as extensive as the author says, what would New York look like without them? Surely it could not have been left in a powerless and brokerless state of chassis and suspended animation.

The author says he is about to do a biography of Fiorello LaGuardia. I suggest to Marie LaGuardia that she be very careful.